For years, archaeologists assumed it was due to regular wear and tear, but it turns out that the real reason so many statues have broken noses is far more intriguing: it was deliberately done!

As is the case with many archaeologists and museum curators, Edward Bleiberg, who oversees the Brooklyn Museum’s Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern collections, presumed that so many ancient Egyptian sculptures had their noses broken due to their age.

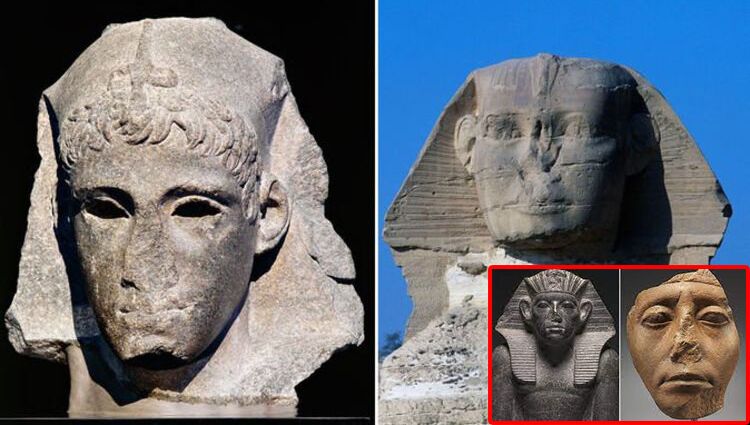

However, when he realized that this was one of the most often asked questions by museum visitors, he decided to investigate further. While it appears obvious that a prominent nose on a three-dimensional statue might be readily knocked off, the plot immediately deepens when you realize that a large number of flat reliefs also have broken noses, which could not have occurred accidentally. Someone is unintentionally doing it, and the question is why?

According to Bleiberg, who is assisting with the curating of an exhibition on the issue, the answer comes in the fact that these sculptures have been deliberately damaged in organized acts of iconoclasm. When you follow the signs, as he argues in Artsy, you see a pervasive pattern of deliberate destruction, all of which go back to the region’s past rulers’ political ambitions.

Egyptian state religion was interpreted as a system in which monarchs made offerings to a deity in exchange for the divinity taking care of Egypt. Sculptures and reliefs frequently depict gods receiving offerings from the elites, and because the ancient Egyptians believed that images of gods and people possessed power (or that the essence or soul of a god or person could inhabit a statue dedicated to them), sculptures played an active role in performing rituals, ‘feeding’ the gods, and retaining power. And actions of iconoclasm have the potential to undermine that authority.

The pattern of destruction immediately indicates that the targets were selected precisely to’deactivate the intensity of an image.’ Smashing a nose renders a statue-spirit incapable of breathing. By hammering the ears off, it would be unable to hear a prayer.

Eliminating divine emblems may have the effect of neutralizing their powers. By chopping off their right hand, they would be unable to receive offerings. And axing the left arm would preclude humans from making sacrifices to gods in sculptures.

Additionally, this flat relief depicts deliberate injury to the nose. Brooklyn Museum

Statues are not the only indications that broken noses are part of a systematic campaign of iconoclasm: there are texts expressing people’s fear of having their statues damaged, decrees from rulers threatening anyone who attempted, instructions on how to eliminate an adversary by creating an effigy and then destroying it, and attempts to safeguard statues by placing them in nooks, on ledges, or enclosing them on all three sides.

While some were defaced to avoid retribution from statue-spirits, as with iconoclasm in general, defacing sculptures aided ambitious rulers (and would-be rulers) by rewriting history to their benefit, erasing the memory of those they sought to replace.

Throughout history, this erasure frequently occurred along gendered lines. The legacies of two of Egypt’s most famous queens – Hatshepsut and Nefertiti – were almost completely erased from visual culture, and serve as a perfect illustration of how images created to legitimize the power of the figure they represent can later be harmed in ways intended to undermine that power.

Hatshepsut reigned as pharaoh alongside her stepson, Thutmose III, following her husband Thutmose II’s early demise.

When Hatshepsut died, Thutmose III desired to establish his own line of succession rather than that of his stepmother, and to crown his son Amenhotep II as pharaoh. As a result, he initiated a campaign to obliterate Hatshepsut’s memory as pharaoh, which he accomplished through a variety of acts of destruction.

For instance, the uraeus, a holy serpent that served as a sign of divine power and was originally mounted to Hatshepsut’s crown, was damaged to negate its protective ability.

Hatshepsut’s beard, a mark of royal legitimacy, was shaved off in order to invalidate her power, and her nose was wounded in order to prevent her spirit from breathing within the sculpture. Finally, the head was removed from the body, completely neutralizing the sculpture’s innate potency.

Additionally, Bleiberg believes the ‘defacers’ were highly trained

individuals paid specifically for the purpose. Accessing and removing specific

pieces of sculpture was no easy task; it required knowledge and, as we have

seen, was most emphatically not accidental.

0 Comments